Refined Datatypes

So far, we have seen how to refine the types of functions,

to specify, for example, pre-conditions on the inputs, or

post-conditions on the outputs. Very often, we wish to define

datatypes that satisfy certain invariants. In these cases, it

is handy to be able to directly refine the data definition,

making it impossible to create illegal inhabitants.

Sparse Vectors Revisited

As our first example of a refined datatype, let’s revisit the sparse

vector representation that we saw earlier. The

SparseN type alias we used got the job done, but is not

pleasant to work with because we have no way of determining the

dimension of the sparse vector. Instead, let’s create a new

datatype to represent such vectors:

Thus, a sparse vector is a pair of a dimension and a list of

index-value tuples. Implicitly, all indices other than those in

the list have the value 0 or the equivalent value type

a.

Sparse vectors satisfy two crucial properties. First,

the dimension stored in spDim is non-negative. Second,

every index in spElems must be valid, i.e. between

0 and the dimension. Unfortunately, Haskell’s type system

does not make it easy to ensure that illegal vectors are not

representable.1

Data Invariants LiquidHaskell lets us enforce these

invariants with a refined data definition:

Where, as before, we use the aliases:

Refined Data Constructors The refined data definition

is internally converted into refined types for the data constructor

SP:

-- Generated Internal representation

data Sparse a where

SP :: spDim:Nat

-> spElems:[(Btwn 0 spDim, a)]

-> Sparse aIn other words, by using refined input types for SP we

have automatically converted it into a smart constructor that

ensures that every instance of a Sparse is legal.

Consequently, LiquidHaskell verifies:

but rejects, due to the invalid index:

Field Measures It is convenient to write an alias for

sparse vectors of a given size N. We can use the field name

spDim as a measure, like vlen. That

is, we can use spDim inside refinements2

Let’s write a function to compute a sparse product

LiquidHaskell verifies the above by using the specification to

conclude that for each tuple (i, v) in the list

y, the value of i is within the bounds of the

vector x, thereby proving x ! i safe.

Folded Product We can port the fold-based

product to our new representation:

As before, LiquidHaskell checks the above by automatically instantiating refinements for the

type parameters of foldl', saving us a fair bit of typing

and enabling the use of the elegant polymorphic, higher-order

combinators we know and love.

Exercise: (Sanitization): Invariants are all well and

good for data computed inside our programs. The only way to

ensure the legality of data coming from outside, i.e. from the

“real world”, is to write a sanitizer that will check the appropriate

invariants before constructing a Sparse vector. Write the

specification and implementation of a sanitizer fromList,

so that the following typechecks:

Hint: You need to check that all the

indices in elts are less than dim; the easiest

way is to compute a new Maybe [(Int, a)] which is

Just the original pairs if they are valid, and

Nothing otherwise.

Exercise: (Addition): Write the specification and

implementation of a function plus that performs the

addition of two Sparse vectors of the same

dimension, yielding an output of that dimension. When you are done, the

following code should typecheck:

Ordered Lists

As a second example of refined data types, let’s consider a different problem: representing ordered sequences. Here’s a type for sequences that mimics the classical list:

The Haskell type above does not state that the elements are in order

of course, but we can specify that requirement by refining

every element in tl to be greater than

hd:

Refined Data Constructors Once again, the refined data

definition is internally converted into a “smart” refined data

constructor

-- Generated Internal representation

data IncList a where

Emp :: IncList a

(:<) :: hd:a -> tl:IncList {v:a | hd <= v} -> IncList awhich ensures that we can only create legal ordered lists.

It’s all very well to specify ordered lists. Next, let’s see how it’s equally easy to establish these invariants by implementing several textbook sorting routines.

First, let’s implement insertion sort, which converts an ordinary

list [a] into an ordered list IncList a.

The hard work is done by insert which places an element

into the correct position of a sorted list. LiquidHaskell infers that if

you give insert an element and a sorted list, it returns a

sorted list.

Exercise: (Insertion Sort): Complete the implementation

of the function below to use foldr to eliminate the

explicit recursion in insertSort.

Merge Sort Similarly, it is easy to write merge sort,

by implementing the three steps. First, we write a function that

splits the input into two equal sized halves:

Second, we need a function that combines two ordered lists

Finally, we compose the above steps to divide

(i.e. split) and conquer (sort and

merge) the input list:

Exercise: (QuickSort): Why is the following

implementation of quickSort rejected by LiquidHaskell?

Modify it so it is accepted.

Hint: Think about how append should

behave so that the quickSort has the desired property. That

is, suppose that ys and zs are already in

increasing order. Does that mean that

append x ys zs are also in increasing order? No!

What other requirement do you need? bottle that intuition into a

suitable specification for append and then ensure

that the code satisfies that specification.

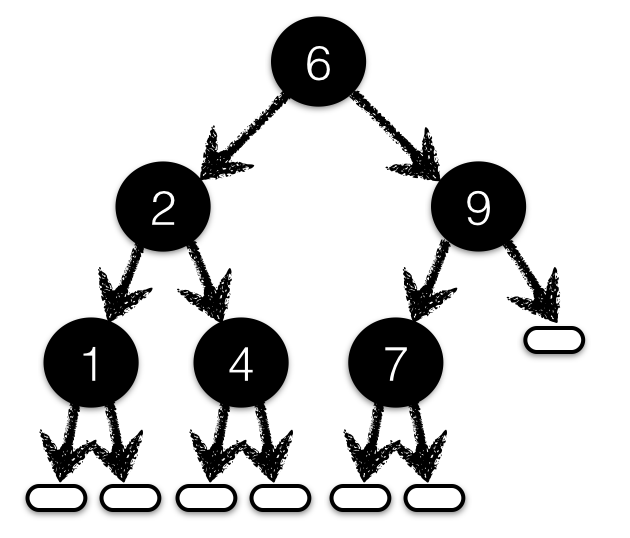

Ordered Trees

As a last example of refined data types, let us consider binary search ordered trees, defined thus:

enjoy the property that

each root lies (strictly) between the elements belonging in

the left and right subtrees hanging off the

root. The ordering invariant makes it easy to check whether a certain

value occurs in the tree. If the tree is empty i.e. a Leaf,

then the value does not occur in the tree. If the given value is at the

root then the value does occur in the tree. If it is less than

(respectively greater than) the root, we recursively check whether the

value occurs in the left (respectively right) subtree.

Figure 1.1 shows a binary search tree whose

nodes are labeled with a subset of values from 1 to

9. We might represent such a tree with the Haskell

value:

Refined Data Type The Haskell type says nothing about

the ordering invariant, and hence, cannot prevent us from creating

illegal BST values that violate the invariant. We can

remedy this with a refined data definition that captures the invariant.

The aliases BSTL and BSTR denote

BSTs with values less than and greater than some

X, respectively.3

Refined Data Constructors As before, the above data

definition creates a refined smart constructor for BST

data BST a where

Leaf :: BST a

Node :: r:a -> BST {v:a| v < r}

-> BST {v:a | r < v}

-> BST awhich prevents us from creating illegal trees

Exercise: (Duplicates): Can a BST Int

contain duplicates?

Lets write some functions to create and manipulate these trees.

First, a function to check whether a value is in a BST:

Singleton Next, another easy warm-up: a function to

create a BST with a single given element:

Insertion Lets write a function that adds an element to

a BST.4

Minimum For our next trick, let’s write a function to

delete the minimum element from a BST. This

function will return a pair of outputs – the smallest element

and the remainder of the tree. We can say that the output element is

indeed the smallest, by saying that the remainder’s elements exceed the

element. To this end, let’s define a helper type: 5

We can specify that mElt is indeed smaller than all the

elements in rest via the data type refinement:

Finally, we can write the code to compute MinPair

Exercise: (Delete): Use delMin to complete

the implementation of del which deletes a given

element from a BST, if it is present.

Exercise: (Safely Deleting Minimum): The function

delMin is only sensible for non-empty trees. Read ahead to learn how to specify and verify

that it is only called with such trees, and then apply that technique

here to verify the call to die in delMin.

Exercise: (BST Sort): Complete the implementation of

toIncList to obtain a BST based sorting

routine bstSort.

Hint: This exercise will be a lot easier

after you finish the quickSort exercise. Note that

the signature for toIncList does not use Ord

and so you cannot (and need not) use a sorting

procedure to implement it.

Recap

In this chapter we saw how LiquidHaskell lets you refine data type definitions to capture sophisticated invariants. These definitions are internally represented by refining the types of the data constructors, automatically making them “smart” in that they preclude the creation of illegal values that violate the invariants. We will see much more of this handy technique in future chapters.

One recurring theme in this chapter was that we had to create new

versions of standard datatypes, just in order to specify certain

invariants. For example, we had to write a special list type, with its

own copies of nil and cons. Similarly, to implement

delMin we had to create our own pair type.

This duplication of types is quite tedious. There

should be a way to just slap the desired invariants on to

existing types, thereby facilitating their reuse. In a few

chapters, we will see how to achieve this reuse by abstracting

refinements from the definitions of datatypes or functions in the

same way we abstract the element type a from containers

like [a] or BST a.

The standard approach is to use abstract types and smart constructors but even then there is only the informal guarantee that the smart constructor establishes the right invariants.↩︎

Note that inside a refined

datadefinition, a field name likespDimrefers to the value of the field, but outside it refers to the field selector measure or function.↩︎We could also just inline the definitions of

BSTLandBSTRinto that ofBSTbut they will be handy later.↩︎While writing this exercise I inadvertently swapped the

kandk'which caused LiquidHaskell to protest.↩︎This helper type approach is rather verbose. We should be able to just use plain old pairs and specify the above requirement as a dependency between the pairs’ elements. Later, we will see how to do so using abstract refinements.↩︎