Several folks who are experts in the program verification literature have asked me some variant of the following question:

How are Liquid/Refinement types different from Floyd-Hoare logics?

This question always reminds me of Yannis Smaragdakis’ clever limerick:

No idea is too obvious or dreary,

If appropriately expressed in type theory,

It’s a research advance,

That no one understands,

But they are all too impressed to be leery.

That is, the above question can be rephrased as: why bother with the hassle of encoding properties in types when good old-fashioned assertions, pre- and post-conditions would do? Is it just a marketing gimmick to make readers too impressed to be leery?

The Problem: Quantifiers

The main algorithmic problem with classical Floyd-Hoare logic is that to do useful things, you need to use universally quantified logical formulas inside invariants, pre- and post-conditions.

Verification then proceeds by asking SMT solvers to check verification conditions (VCs) over these quantified formulas. While SMT solvers are marvelous technological artifacts, and I bow to no one in my admiration of them, in reality, they work best on formulas from a narrowly defined set of decidable theories.

In particular, they are notoriously (and justifiably!) fickle when quizzed on VCs with quantifiers. Briefly, this is because even if the solver “knows” the universally quantified fact:

forall x. P(x)the solver doesn’t know which particular terms e1, e2 or e3

to instantiate the fact at. That is, the solver doesn’t know

which P(e1) or P(e2) or P(e3) it should work with to prove

some given goal. At best, it can make some educated guesses, or

use hints from the user, but these heuristics can turn out to be

quite brittle as the underlying logics

are undecidable in general. To make verification predictable,

we really want to ensure that the VCs remain decidable, and

to do so, we must steer clear of the precipice of quantification.

The Solution: Types

The great thing about types, as any devotee will tell you, is that the compose. Regrettably, that statement is only comprehensible to believers. I prefer to think of it differently: types decompose. To be precise:

Types decompose quantified assertions into quantifier-free refinements.

Let me make my point with some examples that show what verification looks like when using Refinement Types (as implemented in LiquidHaskell) vs Floyd-Hoare style contracts (as implemented in Dafny).

The goal of this exercise is to illustrate how types help with verification, not to compare the tools LH and Dafny. In particular, Dafny could profit from refinement types, and LH could benefit from the many clever ideas embodied within Dafny.

Example 1: Properties of Data

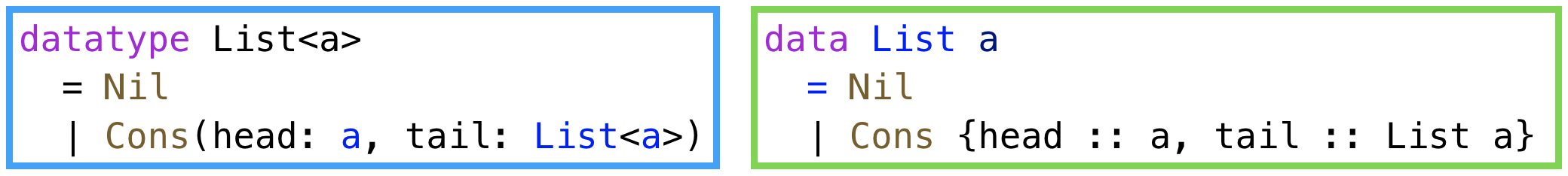

Consider the following standard definition of a List datatype

in Dafny (left) and LH (right).

(You can see the full definitions for Dafny and LiquidHaskell.)

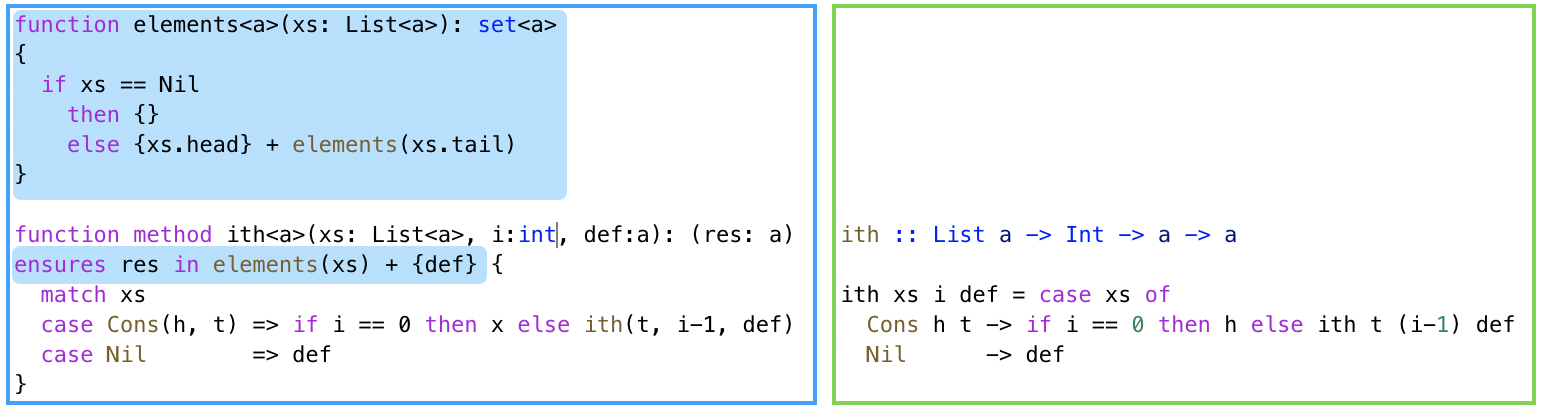

Accessing a list

The two descriptions are more or less the same except for some

minor issues of concrete syntax. However, next consider the

respective implementations of a function to access the ith

element of a List. We also pass in a default value returned

when the index i is invalid.

It is (usually) silly to access lists in this fashion.

I use this example merely to illustrate the common case

of defining a container structure (here, List) and

then accessing its contents (here, ith).

As such, we’d like to specify that the value returned

by the ith element is indeed in the container or is

the default.

Floyd-Hoare Logic

With classical Floyd-Hoare logic, as shown in the Dafny listing

on the left, we must spell out the specification quite explicitly.

The programmer must write an elements function that describes

the set of values in the container, and then the post-condition

of ith states that the res is either in that set or the default.

While this specification seems simple enough, we are already on

dicey terrain: how are we to encode the semantics of the

user-defined function elements to the SMT solver?

In the classical Floyd-Hoare approach, we must use a

quantified invariant of the form:

elements(Nil) = empty

&& forall h t :: elements(Cons(h, t)) = {h} + elements(t)Thanks to the ingenuity of Greg Nelson who invented the notion

of triggers and of Rustan Leino and many others, who devised

ingenious heuristics for using them, Dafny handles the quantifier

calmly to verify the above specification for ith.

However, we are not always so fortunate: it frightfully easy

to run into quantifier-related problems with user-defined

functions, as we will see in due course.

Liquid/Refinement Types

In contrast, the liquid/refinement version is quite spare: there is no extra specification beyond the code. Surely there must be some mistake? Look again: the type signature says everything we need:

If you call

ithwith a list ofavalues and a defaultavalue then you get anavalue”.

That is parametricity removes the overhead of using an

explicit elements function.

Building a list

Next, lets extend our example to illustrate the common

situation where we want some invariant to be true for

all the values in a container. To this end, let us

write a function mkList that builds a container

with values k+1,…,k+n and then test that when

k is non-negative, any arbitrarily chosen value from

the container is indeed strictly positive.

The code in Dafny and LH is more or less the same, except for one crucial difference.

Floyd-Hoare Logic

Recall that the specification for ith(pos, i, 1) states

that the returned value is some element of the container

(or 1). Thus, to verify the assert in testPosN using

classical Floyd-Hoare logic, we need a way to specify that

every element in pos is indeed strictly positive.

With classical program logics, the only way to do so is to

use a universally quantified post-condition, highlighted

in blue:

“for all v if v is in the elements of the result, then v is greater than k”

Liquid/Refinement Types

Regardless of my personal feelings about quantifiers,

we can agree that the version on the right is simpler

as types make it unnecessary to mention elements or

forall. Instead, LH infers

mkList :: Int -> k:Int -> List {v:Int | k < v}That is, that the output type of mkList is a

list of values v that are all greater than k.

The scary forall has been replaced by the friendly

type constructor List. In other words, types

allow us to decompose the monolithic universally

quantified invariant into:

- a quantifier-free refinement

k < v, and - a type constructor that implicitly “quantifies” over the container’s elements.

Lesson: Decomposition Enables Inference

Am I cheating? After all, what prevents Dafny from inferring the same post-condition as LH?

Once again, quantifiers are the villain.

There have been many decades worth of papers on the topic of inferring quantified invariants, but save some nicely circumscribed use-cases these methods turn out to be rather difficult to get working efficiently and predictably enough to be practical. In contrast, once the quantifiers are decomposed away, even an extremely basic approach called Monomial Predicate Abstraction, or more snappily, Houdini, suffices to infer the above liquid type.

Example 2: Properties of Structures

Recall that when discussing the user-defined elements function above,

I had issued some dark warnings about quantifier-related problems that

arise from user-defined functions. Allow me to explain with another

simple example, that continues with the List datatype defined above.

(You can see the full definitions for Dafny and LiquidHaskell.)

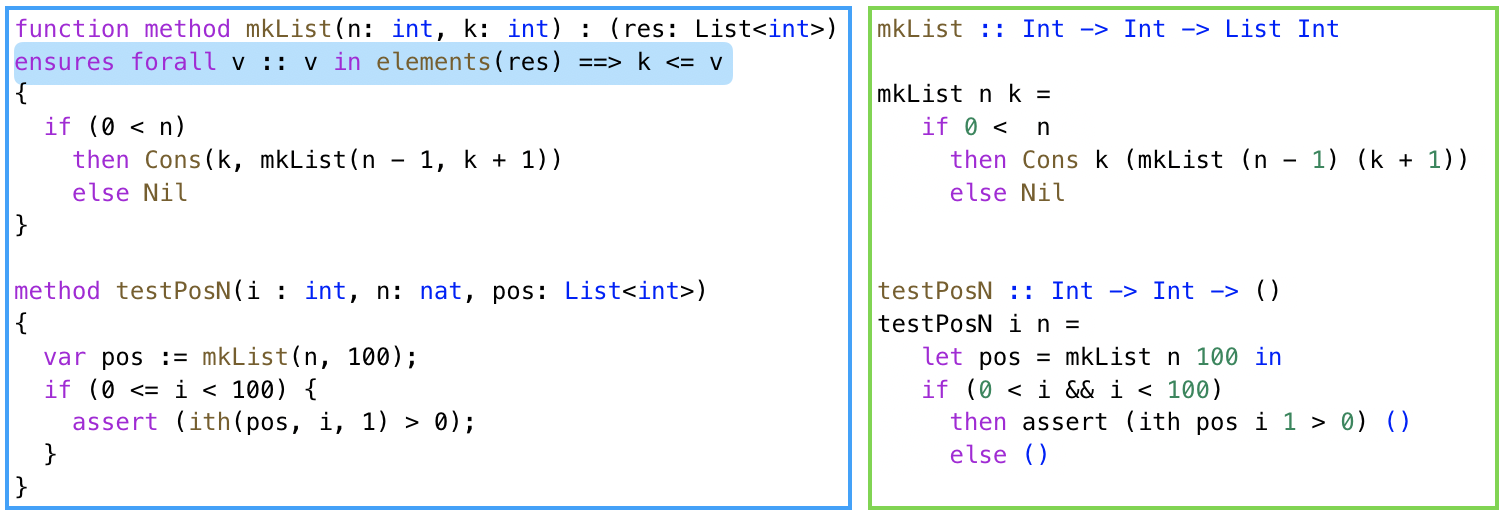

Specifying a size Function

Lets write the usual recursive function that computes the size

of a list. The definitions are mostly identical, except for the green

measure highlight that we will discuss below.

Floyd-Hoare Logic

SMT solvers are restricted to a set of ground theories and hence,

do not “natively” understand user-defined functions. Instead, the

verifer must teach the SMT solver how to reason about formulas (VCs)

containing uses of user-defined functions like size.

In the classical Floyd-Hoare approach, this is done by converting

the definition of size into a universally quantified axiom like:

size Nil == 0 && forall h, t :: size (Cons h t) = 1 + size tA quantifier! By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes…

Liquid/Refinement Types

With a more type-centric view, we can think of the recursive

function size as a way to decorate or refine the types of

the data constructors. So, when you write the definition in

the green box above, specifically when you add the measure

annotation, the function is converted to strengthened

versions for the types of the constructors Nil and Cons,

so its as if we had defined the list type as two constructor

functions

data List a where

Cons :: h:a -> t:List a -> {v:List a | size v == 1 + size t}

Nil :: {v:List a | size v == 0} That is, the bodies of the measures get translated to refinements

on the output types of the corresponding constructors. After this,

the SMT solver “knows nothing” about the semantics of size, except

that it is a function. In logic-speak, size is uninterpreted

in the refinement, and there are no quantified axioms. That is, we

choose to keep SMT solver blissfully ignorant about the semantics

of size. How could this possibly be a good thing?

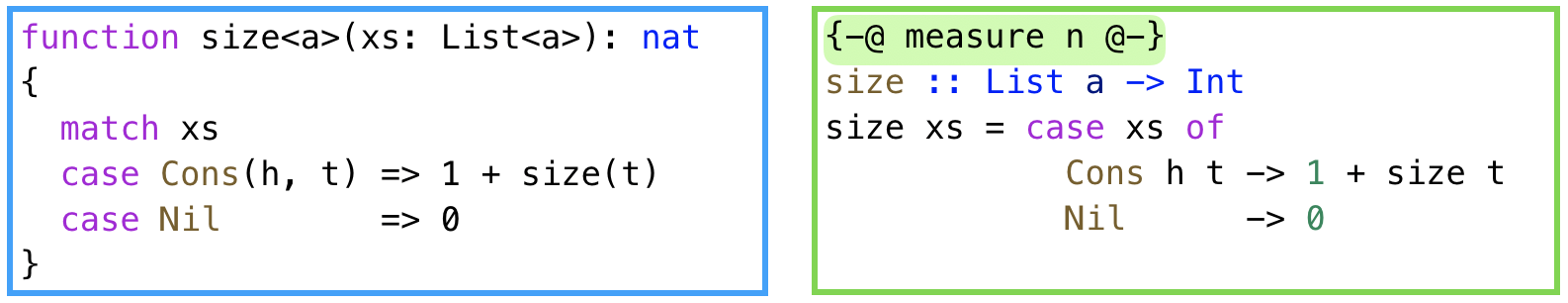

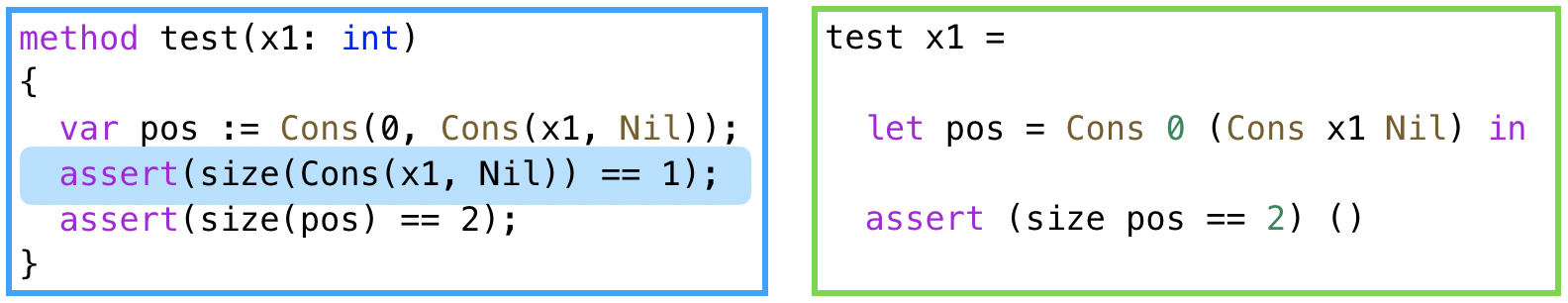

Verifying the size of a List

Next, lets see what happens when we write a simple test that builds

a small list with two elements and asserts that the lists size

is indeed 2:

Floyd-Hoare Logic

To get Dafny to verifier to sign off on the assert (size(pos) == 2)

we have to add a mysterious extra assertion that checks the size of

the intermediate value Cons (1, Nil). (Without it, verification fails.)

Huh? Pesky quantifiers.

The SMT solver doesn’t know where to instantiate the size axom.

In this carefully chosen, but nevertheless simple situation, Dafny’s

instantiation heuristics come up short. I had to help them along by

guessing this intermediate assertion, which effectively “adds” the

fact that the size of the intermediate list is 1, thereby letting

the SMT solver prove the second assertion.

Liquid/Refinement Types

In contrast, with types, the solver is able to verify the code without

batting an eyelid. But how could it possibly do so even though we kept

it ignorant of the semantics of size?

Because types decompose reasoning. In particular, here, the measure

and constructor trick lets us factor reasoning about size into the type system.

In particular, LH internally views the code for test in A-Normal Form

which is a fancy way of saying, by introducing temporary variables

for all sub-expressions:

test x1 =

let tmp0 = Nil

tmp1 = Cons x1 tmp0

pos = Cons 0 tmp1

in

assert (size pos == 2)And now, just by the rules of type checking, and applying the types of the constructors, it deduces that:

tmp0 :: {size tmp0 == 0}

tmp1 :: {size tmp1 == 1 + size tmp0}

pos :: {size pos == 1 + size tmp1}which lets the SMT solver prove that size pos == 2 without

requiring any axiomatic description of size. This simple

measure method goes a very long way in specifying and

verifying lots of properties.

Lesson: Decomposition Enables Type-Directed Instantiation

I’d like to emphasize again that this trick was enabled by the type-centric view: encode the function semantics in data constructors, and let the type checking (or VC generation) do the instantiation.

It could easily by incorporated inside and work together with axioms in Floyd-Hoare based systems like Dafny. Of course, this approach is limited to a restricted class of functions – roughly, case-splits over a single data type’s constructors – but we can generalize the method quite a bit using the idea of logical evaluation.

Summary

To sum up, we saw two examples where taking a type-centric view made verification more ergonomic, essentially by factoring reasoning about quantifiers into the type system.

In the first case, when reasoning about data in containers, the polymorphic type constructor

Listprovided an natural way to reason about the fact that all elements in a container satisfied some property.In the second case, when reasoning about the structure of the container via a recursive function, the types of the data constructors allowed us to factor the instantiation of properties of

sizeat places where the list was constructed (and dually, not shown, destructed) without burdening the SMT solver with any axioms and the pressure of figuring out where to instantiate them.

To conclude I’d like to reiterate that the point is not that types and program logics are at odds with each other. Instead, the lesson is that while classical Floyd-Hoare logic associates invariants with program positions, Liquid/Refinement types are a generalization that additionally let you associate invariants with type positions, which lets us exploit

- types as a program logic, and

- syntax-directed typing rules as a decision procedure,

that, in many common situations, simplify verification by

decomposing proof obligations (VCs) into simple, quantifier-free,

SMT-friendly formulas. As you might imagine, the benefits

are magnified when working with higher-order functions,

e.g. map-ing or fold-ing over containers…

Acknowledgments

Huge thanks to Rustan Leino, Nadia Polikarpova, Daniel Ricketts, Hillel Wayne, and Zizz Vonnegut for patiently answering my many questions about Dafny!